Another Tragedy Grips a High School

John Odgren was enrolled in a class on forensic science at his high school, in one of Boston's bucolic suburbs. Always awkward with his classmates, John had started wearing a trench coat and fedora to school. Students who tried to befriend him were put off by his obsession with knives and common discussion of violence. During one class session, John outlined his plan for the perfect murder, which involved luring a trusting acquaintance to a remote location and using a knife to kill him. Classmates were freaked out by John's seemingly cold-hearted calculation and devious planning. As it turned out, they had every reason to be.

Not long afterwards, John Odgren followed a shy sophomore, new to the school, into a bathroom and stabbed him to death with a long knife he had brought to school. Odgren told investigators that he had brought the knife in for protection, convinced by the symbolism in a Stephen King novel that something horrible would happen to him that day. Another student, who just happened to be in one of the stalls, heard the victim call out, "Ow! You're hurting me! Why are you doing this?" The student emerged to find John Odgen sitting on the bathroom floor, knees pulled up to his chest, holding the bloody knife.

As horrifying as this scene is, there would seem to be little remarkable about it from a criminal justice perspective. One person committed a completely unprovoked act of violence against another. The outcome would seem to be clear.

The Psychology of Intent

There is, however, one significant wrinkle to this story. John Odgren has been diagnosed with Asperger's Syndrome, which lies along the autism scale. Asperger's sufferers are usually characterized by normal to high intelligence (Odgren allegedly has an IQ of 140), but the inability to experience the empathy necessary to form emotional bonds with others. This disability is often manifested in, among other things, the inability to recognize emotional expressions in others. That is, while you or I can distinguish a smile from a frown (and what each implies), someone with Asperger's Syndrome cannot.

In Massachusetts, the mens rea requirement for first-degree murder is "deliberate and premeditated malice." For second-degree murder, a killer must have experienced "malice aforethought."

Malice aforethought is generally defined as: "the conscious intent to cause death or great bodily harm to another person before a person commits the crime." Note that it must be a conscious intent. So, if a person forms the intent in a hallucinogenic haze, it does not suffice for malice aforethought.

John Odgren is employing an insanity defense to the murder charge, claiming that his psychological condition (He also has ADHD, a bipolar disorder and possibly OCD) precluded his ability to consciously form the necessary intent to commit murder. Massachusetts has adopted the Model Penal Code definition of "legal insanity." Under this test, "a person is not responsible for criminal conduct if, at the time of such conduct, as a result of mental disease or defect, he lacks substantial capacity either to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of the law."

Jury must determine criminal culpability

This murder case then will boil down to a jury's collective decision about whether John Odgren did or did not appreciate the wrongfulness of his actions on the day that he stabbed that fellow student. The trial itself is now complete. The arguments followed fairly predictable lines. The DA emphasized the calculating nature of the crime and its similarities to what John Odgren seems to have been considering for weeks. The defense focused on Odgren's myriad psychological problems, constant harassment at school and increasing obsession with violent books, movies and video games. The defense presented three psychologists who testified that Odgren committed the violent act while essentially in an obsessive trance. They concluded that he was essentially shocked back to reality by observing the horrific consequences of his actions. The DA presented a rebuttal expert who, while not disputing the general diagnoses of Odgren's conditions, concluded he was nonetheless capable of discerning right from wrong.

There are actually two questions to be answered. Even if the jury determines that John Odgren understood the criminality of his actions, the jurors must wrestle with the question of whether he was psychologically capable of resisting his persistent violent urges and compulsions. The final item presented by the DA during closing arguments was an audio recording of Odgren laughing about what investigators found while searching his bedroom. This is intended to show a lack of remorse and an arrogance by Odgren about his ability to get away with the crime. Such callousness can cut both ways, however, as jurors might conclude that anyone who could react that way while in prison for murder must be out of touch with reality.

The need to make sense out of chaos

I believe that the defense strategy in this case was incomplete.

The defense team did a fairly good job of portraying Odgren as a thoroughly disturbed teenager with a history of mental problems. This is an important linchpin of the case, as it provides an opportunity for those jurors who don't want to hold him responsible to make their arguments. A "not guilty by reason of insanity" vote passes the proverbial sniff test.

Unfortunately, this only provides jurors with half of what they need to achieve emotional satisfaction from a not guilty vote. People need order in their lives. They need to be able to make sense of the world around them. They need to feel some control over their environment. Without this sense of control, life becomes unbearable. This explains, in part, people's visceral fear of the unknown. It also explains attachments to rituals, customs, religions and other systems that preserve the status quo.

The tragic death at the center of this case -- violent, senseless, seemingly random -- must seriously disturb the jurors' need for order and control. It is a parent's worst nightmare -- the loss of a child in a way that no parent can anticipate. The natural response of the jurors in this case will be to try to impose order on the situation. The idea that this was a freakish, unanticipated, random tragedy, for which no-one is really responsible, will be a completely unbearable option for the jurors. It just won't do.

So, the defense has provided the jurors with reasons not to blame John Odgren for this tragedy. What the defense has failed to do is provide them with someone else to blame. Trust me on this one: the jurors will need to blame someone. The only question is whether they will blame John Odgren or someone else.

had I been advising the defense team in this case, I would have recommended telling a somewhat different story. This is the narrative I would have crafted:

There are two victims in this crime. The dead boy and John Odgren were both failed by a system that too often shuffles emotionally ill children from program to program, treating them like human guinea pigs, testing out their most recent theories of mainstreaming or immersive learning. The so-called experts in this case didn't protect John Odgren from the bullies. They didn't protect John Odgren from the demons in his head. They didn't protect him from himself. And because of their failures, one boy is dead and another might as well be, ruined for life by a disaster that didn't have to happen. The signs were there for years. The thoughts of suicide. The absence of emotional control. The inability to feel any emotions but fear and anger and hate. The psychologists and teachers and school administrators weren't in that bathroom on that terrible, fateful day, but they might as well have been, handing John Odgren his knife.

Would this argument have worked in this case? We will never know (although I suppose we could run some focus group research in other parts of the country). What I do know is that these jurors need a way to direct their grief and their fear and their anger, someone to hold responsible. They need to be able to wrap their brains around the case and conclude that they have identified the villain. The defense had a responsibility to their client to give the jury someone else to blame.

Jurors will speculate about lots of things. Nothing precludes them from assigning blame all over the map in this case, regardless of whether the defense has pointed its finger at any particular candidates. Perhaps the jurors will find their own way to sparing John Odgren in this case. If they do -- if they find him not guilty -- I fully expect to discover that they did so by assigning blame elsewhere.

As the verdict comes in, I will be sure to report it here on my blog. I'll offer some post-trial comments and I'll keep you abreast of any juror interviews that appear in the press.

Recent Jury Box Blog Entries

Subscribe to The Jury Box Blog

Wednesday, April 28, 2010

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

Trial Strategy can be as much about When as What

Two Defendants, Two Trials

As followers of The Jury Box Blog know, I have been blogging and tweeting regularly about the trials of Michael and Carolyn Riley, who were both accused of murdering their four-year-old daughter, Rebecca, by administering to her dangerously high doses of ADHD medicine, and then refusing to seek medical attention when she fell deathly ill.

Originally, the pair was scheduled to be tried together. Shortly before jury selection was scheduled to begin, defense counsel made a motion for separate trials, on the grounds that each was likely to implicate the other in mounting a defense. The district attorney did not object and the judge granted the request, recognizing the potential conflict of interest.

The district attorney was then faced with a new set of tasks. Rather than convincing one jury that the couple acted in concert, he had to convince one jury that Carolyn was responsible and then a completely different jury that Michael was responsible.

Who should go first?

Facing the prospect of successive trials, the DA had at his disposal one strategic lever. He got to decide the order in which the defendants would be tried. Before reading further, consider what you would have done? Who goes first?

The DA decided to try Carolyn first, followed by Michael. I think this was a wise strategy (and not just because it worked). At the time, I remember thinking how shrewd this was. Here's why:

Despite best efforts to select jurors in the second trial who are not informed about what happened in the first trial, it is impossible to do so with any confidence. Therefore, the DA had to think about the consequences of the first verdict on the second trial. The first step in the process is to consider the relative culpabilities of the two defendants.

Carolyn Riley is something of an enigma. She seems emotionally detached and not especially bright. There were times during recorded interviews when she didn't seem to really understand what was going on. While Carolyn certainly was not as caring towards her children as one would have hoped, she did not seem to have the mean streak that characterized Michael's personality. In many ways, she seemed to be in fear of her husband. Michael Riley had even been forced by court order to leave their family home at a previous location.

While it might have been a long-shot, it was not out of the question for Carolyn's defense team to mount an insanity defense. Who knows whether her kids were actually mentally ill in any way, but Carolyn clearly had some serious cognitive and emotional problems. So, while Carolyn seems to have actually performed more physical acts that contributed to Rebecca's death, she cut a more sympathetic figure than did her husband, Michael.

Consequences of First Trial on Second Jury

As a result of these factors, it seemed to be a safer bet to secure a conviction against Michael than against Carolyn. With this in mind, it definitely made sense to try Carolyn first. Consider the possible outcomes of Carolyn's trial. If she had been found not-guilty, the jury in Michael's trial would have felt particularly compelled to hold someone responsible for the senseless tragedy of Rebecca's death. If Carolyn had been found guilty of some lesser offense (as she was, in the end), the jury could certainly find room to decide that Michael was even more at fault. If Carolyn had been found guilty of first-degree murder, Michael's jury might have reasoned that he was at least as responsible and that fairness required the same verdict for him. So, trying Carolyn first would not interfere with the prosecution of Michael and might even help the case.

On the other hand, trying Michael first might have posed some problems for the prosecution against Carolyn. Had Michael been found not-guilty, Carolyn's jury would have likely considered it completely unfair to convict her of something for which her abusive husband got off scot-free. This dynamic pops up a lot in criminal cases. When an accomplice turns state's evidence and gets a cushy deal, a jury is sometimes reluctant to convict the defendant of anything too serious, on the grounds that the outcomes for the two are unfairly disparate. Jurors often don't even realize that they are applying such a "relative justice" metric.

Even if Michael Riley were tried first and convicted, Carolyn's trial team would play up the degree of dominance he exerted over the family. A juror who was looking for a reason to show mercy to Carolyn could seize on Michael's conviction as justification for leniency with respect to Carolyn. Since the "real bad guy" has already been convicted and Rebecca's murder will not go unpunished, a juror would be able to more easily justify (to herself and fellow jurors) going easy on Carolyn.

Applying Lessons Learned

It is, of course, easy to look brilliant playing Monday morning quarterback. The DA did, in fact, try Carolyn first. The defense never raised the issue of Carolyn's own mental state. The Commonwealth secured a conviction on Second Degree Murder. The subsequent trial of Michael Riley was quite unremarkable, relying on similar tactics as had been used unsuccessfully in Carolyn's trial. The two main defense tactics were to contest the Coroner's conclusion that Rebecca died from the drug overdose, rather than the pneumonia from which she was suffering, and pinning as much blame as possible on the Tufts staff psychologist who had prescribed Rebecca's medicine without conducting a thorough evaluation of the child. The major flaw in this approach was its failure to address the severe neglect of Rebecca in her final hours, as she begged for help while dying in her own home. At some level, I don't think the jurors cared as much about what killed her as they did about how her parents just let her die because they couldn't be bothered to get her medical care.

The outcomes of these cases, however, were far from a certainty. The DA did a good job, including the decision to try the defendants in the strategically sensible order. There is an important lesson here. Procedural decisions can have important strategic consequences. They should not be made lightly, or based solely on convenience.

When things go wrong with a pharmaceutical, it often triggers a whole series of lawsuits. A plaintiffs' attorney might have several cases against the same company. In addition to deciding on the best venue for bringing the suits, the lawyer should also think hard about the order in which she wants to bring the cases.

There is a high-profile case developing up here in Massachusetts, involving a high school student who hung herself after prolonged bullying by classmates. Criminal charges have been filed against nine different students, some of whom are charged as adults. The DA will have an interesting dilemma with respect to the order in which to prosecute these cases. Not all of the defendants are charged with the same crimes (a couple of boys are charged with statutory rape) and they seemed to have directed varying degrees of hostility towards the victim. It will be interesting to see the order in which the DA decides to proceed.

As followers of The Jury Box Blog know, I have been blogging and tweeting regularly about the trials of Michael and Carolyn Riley, who were both accused of murdering their four-year-old daughter, Rebecca, by administering to her dangerously high doses of ADHD medicine, and then refusing to seek medical attention when she fell deathly ill.

Originally, the pair was scheduled to be tried together. Shortly before jury selection was scheduled to begin, defense counsel made a motion for separate trials, on the grounds that each was likely to implicate the other in mounting a defense. The district attorney did not object and the judge granted the request, recognizing the potential conflict of interest.

The district attorney was then faced with a new set of tasks. Rather than convincing one jury that the couple acted in concert, he had to convince one jury that Carolyn was responsible and then a completely different jury that Michael was responsible.

Who should go first?

Facing the prospect of successive trials, the DA had at his disposal one strategic lever. He got to decide the order in which the defendants would be tried. Before reading further, consider what you would have done? Who goes first?

The DA decided to try Carolyn first, followed by Michael. I think this was a wise strategy (and not just because it worked). At the time, I remember thinking how shrewd this was. Here's why:

Despite best efforts to select jurors in the second trial who are not informed about what happened in the first trial, it is impossible to do so with any confidence. Therefore, the DA had to think about the consequences of the first verdict on the second trial. The first step in the process is to consider the relative culpabilities of the two defendants.

Carolyn Riley is something of an enigma. She seems emotionally detached and not especially bright. There were times during recorded interviews when she didn't seem to really understand what was going on. While Carolyn certainly was not as caring towards her children as one would have hoped, she did not seem to have the mean streak that characterized Michael's personality. In many ways, she seemed to be in fear of her husband. Michael Riley had even been forced by court order to leave their family home at a previous location.

While it might have been a long-shot, it was not out of the question for Carolyn's defense team to mount an insanity defense. Who knows whether her kids were actually mentally ill in any way, but Carolyn clearly had some serious cognitive and emotional problems. So, while Carolyn seems to have actually performed more physical acts that contributed to Rebecca's death, she cut a more sympathetic figure than did her husband, Michael.

Consequences of First Trial on Second Jury

As a result of these factors, it seemed to be a safer bet to secure a conviction against Michael than against Carolyn. With this in mind, it definitely made sense to try Carolyn first. Consider the possible outcomes of Carolyn's trial. If she had been found not-guilty, the jury in Michael's trial would have felt particularly compelled to hold someone responsible for the senseless tragedy of Rebecca's death. If Carolyn had been found guilty of some lesser offense (as she was, in the end), the jury could certainly find room to decide that Michael was even more at fault. If Carolyn had been found guilty of first-degree murder, Michael's jury might have reasoned that he was at least as responsible and that fairness required the same verdict for him. So, trying Carolyn first would not interfere with the prosecution of Michael and might even help the case.

On the other hand, trying Michael first might have posed some problems for the prosecution against Carolyn. Had Michael been found not-guilty, Carolyn's jury would have likely considered it completely unfair to convict her of something for which her abusive husband got off scot-free. This dynamic pops up a lot in criminal cases. When an accomplice turns state's evidence and gets a cushy deal, a jury is sometimes reluctant to convict the defendant of anything too serious, on the grounds that the outcomes for the two are unfairly disparate. Jurors often don't even realize that they are applying such a "relative justice" metric.

Even if Michael Riley were tried first and convicted, Carolyn's trial team would play up the degree of dominance he exerted over the family. A juror who was looking for a reason to show mercy to Carolyn could seize on Michael's conviction as justification for leniency with respect to Carolyn. Since the "real bad guy" has already been convicted and Rebecca's murder will not go unpunished, a juror would be able to more easily justify (to herself and fellow jurors) going easy on Carolyn.

Applying Lessons Learned

It is, of course, easy to look brilliant playing Monday morning quarterback. The DA did, in fact, try Carolyn first. The defense never raised the issue of Carolyn's own mental state. The Commonwealth secured a conviction on Second Degree Murder. The subsequent trial of Michael Riley was quite unremarkable, relying on similar tactics as had been used unsuccessfully in Carolyn's trial. The two main defense tactics were to contest the Coroner's conclusion that Rebecca died from the drug overdose, rather than the pneumonia from which she was suffering, and pinning as much blame as possible on the Tufts staff psychologist who had prescribed Rebecca's medicine without conducting a thorough evaluation of the child. The major flaw in this approach was its failure to address the severe neglect of Rebecca in her final hours, as she begged for help while dying in her own home. At some level, I don't think the jurors cared as much about what killed her as they did about how her parents just let her die because they couldn't be bothered to get her medical care.

The outcomes of these cases, however, were far from a certainty. The DA did a good job, including the decision to try the defendants in the strategically sensible order. There is an important lesson here. Procedural decisions can have important strategic consequences. They should not be made lightly, or based solely on convenience.

When things go wrong with a pharmaceutical, it often triggers a whole series of lawsuits. A plaintiffs' attorney might have several cases against the same company. In addition to deciding on the best venue for bringing the suits, the lawyer should also think hard about the order in which she wants to bring the cases.

There is a high-profile case developing up here in Massachusetts, involving a high school student who hung herself after prolonged bullying by classmates. Criminal charges have been filed against nine different students, some of whom are charged as adults. The DA will have an interesting dilemma with respect to the order in which to prosecute these cases. Not all of the defendants are charged with the same crimes (a couple of boys are charged with statutory rape) and they seemed to have directed varying degrees of hostility towards the victim. It will be interesting to see the order in which the DA decides to proceed.

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

Heat, Humidity and Trial Consulting: What Services Lawyers Use Where

What we've learned so far

To review, I posted a short survey about trial and graphics consultant usage by trial attorneys. I encourage those who have not yet taken the survey to check it out here. In my previous two posts (Post 1, Post 2), I reviewed some general trends in the data. While the number of respondents (42) precludes any concrete conclusions, the data are at least suggestive.

More experienced attorneys were more likely to report having used trial consulting and graphics consulting services at some point in their careers. This is not surprising since a lawyer who has tried a large number of cases is likely to have run across at least one along the way that warranted the hiring of a jury expert or graphics professional. In addition, litigants in high-stakes cases, where the hiring of outside consultants seems most likely, typically choose to place their cases in the hands of experienced litigators. Similarly, large firms generally assign their largest cases to their most experienced lawyers.

The second major finding is that civil defense attorneys are more likely to hire trial and graphics consultants than are their colleagues who handle plaintiffs' cases. Many of the criminal defense attorneys who participated in the survey reported having used a trial consultant, but this result is likely skewed by the large number of them who had taken advantage of my Pro Bono services. Many fewer of them reported having employed a graphics consultant.

Who Wants What When?

Note the frequent usage of both case evaluation and jury selection services by criminal defense attorneys. This is, once again, the product of this category of respondents being dominated by attorneys who have received pro bono assistance from me, which has taken the form of case evaluations and jury selection help. It remains an open question whether these are the services most often employed by criminal defense attorneys more generally.

Where is all the action?

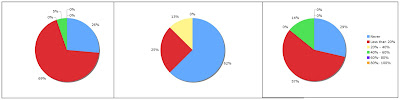

When breaking the sample into regions, things got a bit dicey. With only a few dozen lawyers completing the survey, it was simply not possible to sensibly explore which regions' litigators used precisely which services. I did look into using only civil defense attorneys to investigate regional differences, but what few trends emerged mirrored those present in the full sample. I illustrate below trial and graphic consultant usage by region, without attention paid to specific services.

In considering these graphs, it is important to keep in mind the mix of attorneys represented in each region. The West, Mideast and South regions are comprised of 1/2 to 2/3 civil defense attorneys. The New England region sample is dominated by criminal defense attorneys and only contains two civil defense attorneys. The Midwest sample is entirely civl defense attorneys.

With all these caveats, are there any comparisons to be made, at all? Well, it is instructive to look at the responses of attorneys in the Mideast and South regions. The sample sizes are comparable, as are the distributions across legal specialties. Note, however, how much more likely a lawyer from the Mideast region is to report that she had never used either a trial or graphics consultant. There is one young lawyer from New York who reported extremely high usage rates for both trial and graphics services, as well as a strange mix of case types. If one drops this observation as unreliable, the differences between the two regions become even more pronounced.

Anecdotally, I know Florida, Georgia and Texas to be hotbeds of trial consultant activity. There are, however, several trial consulting firms with offices in the tri-state region (near New York City). As such, I am a bit surprised by these dramatic differences.

What next?

I designed this little survey to gather some preliminary information and motivate further study. I think that it has served to accomplish that task. I know that the Research Committee of the American Society of Trial Consultants has plans to conduct a broader and deeper study of these issues in the near future. To that end, if you have suggestions for questions to ask, lawyers groups to approach for participation or groups that would be interested in the results, please let me know. I will forward along all correspondence to the Research Committee.

While a data dude at heart, I know the value of qualitative research, too. So, if you have any questions about this survey or comments about my analysis, please do get in touch. Tell me your story. Share your concerns.

In the meantime, I will leave the survey open for further respondents. If I get enough additional data, I'll post an update here on my blog.

To those of you who took the time to complete the survey, "Thanks very much for your help."

-Edward

To review, I posted a short survey about trial and graphics consultant usage by trial attorneys. I encourage those who have not yet taken the survey to check it out here. In my previous two posts (Post 1, Post 2), I reviewed some general trends in the data. While the number of respondents (42) precludes any concrete conclusions, the data are at least suggestive.

More experienced attorneys were more likely to report having used trial consulting and graphics consulting services at some point in their careers. This is not surprising since a lawyer who has tried a large number of cases is likely to have run across at least one along the way that warranted the hiring of a jury expert or graphics professional. In addition, litigants in high-stakes cases, where the hiring of outside consultants seems most likely, typically choose to place their cases in the hands of experienced litigators. Similarly, large firms generally assign their largest cases to their most experienced lawyers.

The second major finding is that civil defense attorneys are more likely to hire trial and graphics consultants than are their colleagues who handle plaintiffs' cases. Many of the criminal defense attorneys who participated in the survey reported having used a trial consultant, but this result is likely skewed by the large number of them who had taken advantage of my Pro Bono services. Many fewer of them reported having employed a graphics consultant.

Who Wants What When?

I was not surprised that civil defense attorneys were the primary consumers of trial consulting services. They typically have an insurance company bankrolling litigation and are more likely to have corporate clients. So, the deep-pocket, repeat-player litigants tend to be on the defense side of the ledger.

I also expected to find that civil defense attorneys used a different mix of trial consulting services than did their plaintiff counterparts. This was not born out by the data. Consider the following graph. You can click on any graph to view it much larger.

Because civil defense attorneys make up such a large fraction of my sample, these absolute numbers are a bit deceiving. To correct for this, I converted these data into percentage of the relevant sample. The reconfigured graph is below.

Those plaintiff attorneys who reported using trial consulting services were just as likely to report running mock trials (a big ticket item) as were civil defense attorneys. One possibility is that once the stakes cross a critical threshold, a plaintiff attorney thinks just like a defense lawyer. That is, there is an "all or nothing" mentality to trial consultant usage. The other possibility is that many plaintiffs' attorneys are unaware that trial consultants provide a suite of inexpensive services, as well as conducting large pre-trial research projects. That is, a plaintiff attorney might know that she can hire a consultant to run a mock trial for $30,000, but she might not know that she can hire one to help draft voir dire questions for $1,000. This is a question for further study.

Note the frequent usage of both case evaluation and jury selection services by criminal defense attorneys. This is, once again, the product of this category of respondents being dominated by attorneys who have received pro bono assistance from me, which has taken the form of case evaluations and jury selection help. It remains an open question whether these are the services most often employed by criminal defense attorneys more generally.

Where is all the action?

When breaking the sample into regions, things got a bit dicey. With only a few dozen lawyers completing the survey, it was simply not possible to sensibly explore which regions' litigators used precisely which services. I did look into using only civil defense attorneys to investigate regional differences, but what few trends emerged mirrored those present in the full sample. I illustrate below trial and graphic consultant usage by region, without attention paid to specific services.

In considering these graphs, it is important to keep in mind the mix of attorneys represented in each region. The West, Mideast and South regions are comprised of 1/2 to 2/3 civil defense attorneys. The New England region sample is dominated by criminal defense attorneys and only contains two civil defense attorneys. The Midwest sample is entirely civl defense attorneys.

With all these caveats, are there any comparisons to be made, at all? Well, it is instructive to look at the responses of attorneys in the Mideast and South regions. The sample sizes are comparable, as are the distributions across legal specialties. Note, however, how much more likely a lawyer from the Mideast region is to report that she had never used either a trial or graphics consultant. There is one young lawyer from New York who reported extremely high usage rates for both trial and graphics services, as well as a strange mix of case types. If one drops this observation as unreliable, the differences between the two regions become even more pronounced.

Anecdotally, I know Florida, Georgia and Texas to be hotbeds of trial consultant activity. There are, however, several trial consulting firms with offices in the tri-state region (near New York City). As such, I am a bit surprised by these dramatic differences.

What next?

I designed this little survey to gather some preliminary information and motivate further study. I think that it has served to accomplish that task. I know that the Research Committee of the American Society of Trial Consultants has plans to conduct a broader and deeper study of these issues in the near future. To that end, if you have suggestions for questions to ask, lawyers groups to approach for participation or groups that would be interested in the results, please let me know. I will forward along all correspondence to the Research Committee.

While a data dude at heart, I know the value of qualitative research, too. So, if you have any questions about this survey or comments about my analysis, please do get in touch. Tell me your story. Share your concerns.

In the meantime, I will leave the survey open for further respondents. If I get enough additional data, I'll post an update here on my blog.

To those of you who took the time to complete the survey, "Thanks very much for your help."

-Edward

Wednesday, March 10, 2010

Different Strokes for Different Folks: Consultant Usage varies by specialty and experience

Digging Deeper in the Data

In my last post, I reviewed some general trends in the data from my survey of trial and graphics consultant usage by trial attorneys. As I mentioned in the last post, the survey is completely confidential and only takes about 2 minutes to fill out. Several lawyers responded to my invitation and followed this link to participate in the survey. As such, the data I review today includes a few more observations. The more the merrier, so please take the survey if you have not yet done so!

In perusing the data, I noticed a few interesting trends. These relate to how long a respondent has been practicing law, what kind of cases she handles and where her office is located. I now turn to some of these trends.

Youth vs. Experience

One might expect that young lawyers would be more likely to hire trial and graphics consultants because these folks have grown up in the "high-tech" era. Everything in their lives has been accompanied by fancy graphics and animation. These young lawyers also went to law school after the adoption of the interdisciplinary approach to legal education. A lawyer under 50 years of age is more likely to have been taught by dual-degree professors and might, therefore, have a greater appreciation for the value of psychology and other social sciences in litigation.

As illustrated in the graphs below, this expectation is not born out in the data.

Trial Consultant Usage by Attorneys

More than 15 years experience Less than 15 years Experience

Graphics Consultant Usage by Attorneys

More than 15 years Experience Less than 15 years Experience

Trial lawyers with more than 15 years of experience were much more likely to report having employed a trial consultant or graphics consultant than their younger colleagues. So, what do we make of these results?

I think that there are a few factors at work here. First of all, a more experienced litigator will have handled a larger number of cases. As such, she is more likely to have come across some case along the way that seemed to require the expertise of an outside consultant, with respect to either jury or graphics issues.

Second, more experienced litigators tend to handle the higher stakes cases. This is both because litigants with a lot on the line seek out experienced litigators and because large firms assign their highest stakes cases to their most experienced lawyers. These high stakes cases are the ones for which lawyers see the most justification for incurring the expense of a trial or graphics consultant.

Exactly one respondent indicated that she uses a trial consultant in more than half of her cases. She is also the one lawyer who said she uses a graphics consultant more than half the time. This litigator has been practicing for less than five years, supporting, at least anecdotally, the "new breed of lawyer" hypothesis.

Cost Conscious Courtroom Counsellors

In the previous section, I raised for the first time the influence clients can have on their attorneys' trial strategy decisions. The survey sample is made up almost entirely of three kinds of trial lawyers, with different kinds of clients. More than half of the respondents handle predominantly civil defense cases. The remainder is roughly evenly divided between plaintiffs' attorneys and criminal defense attorneys. The differences in reported trial and graphics consultant usage among these three groups is quite remarkable.

Trial Consultant Usage by Attorneys by Primary Practice Area

Civil Defense Civil Plaintiff Criminal Defense

Civil defense attorneys are very often hired by insurance companies, who are the ultimate deep-pocket, repeat players in the judicial system. Handling thousands of trials annually, insurance company risk managers understand the value of pretrial research, witness preparation and well-designed jury selection strategy. A litigator might not be inclined to reach out to a consultant for advice, figuring that she has all the tools she needs to win a case. When an insurance company claims supervisor tells that litigator to run a focus group study, she does as she is told. From a personal perspective, I know that many civil defense attorneys call me because an insurance company has told them to "get your jury guy on the phone and set up a mock trial." Under such an arrangement, the litigator incurs none of the cost associated with hiring a consultant.

By contrast, most plaintiffs' attorneys reported having never used a trial consultant. This should not be surprising, given that their clients tend to have less money to work with. In addition, many plaintiffs, having never been involved in a trial before, have unrealistic expectations about the cost of litigation. A plaintiff attorney is under enormous pressure to keep costs down. The financial situation facing a plaintiff attorney tends to differ from that of the defense attorney on the other side of the aisle. Many plaintiffs' attorneys are solo practitioners or members of very small firms, handling mostly small cases. When a high stakes case does come along, such an attorney faces severe cash flow problems financing the litigation. While such a lawyer might very much want to hire a trial or graphics consultant, she might simply not have access to the funds to do so. I know that many of us in the trial consulting community have attempted to implement creative fee structures to make our services more available to plaintiffs' attorneys.

The graph representing trial consulting usage by criminal defense attorneys is probably quite misleading. I head the New England Team of the pro bono initiative of the American Society of Trial Consultants (ASTC). In this capacity, I have been running free clinics for criminal defense attorneys here in Massachusetts. I know that 3 of the 5 criminal defense lawyers who report having used a trial consultant are folks I have personally helped as part of this pro bono initiative. I would need a much larger, and geographically diverse, sample to know how common it is for criminal defense attorneys to use trial consultants.

By comparison, the data on graphics consultant usage should be more reliable.

Graphics Consultant Usage by Attorneys by Primary Practice Area

Civil Defense Civil Plaintiff Criminal Defense

The discrepancy between civil plaintiff and defense attorney resource usage is even more pronounced with respect to graphics consulting. A quarter of civil defense attorneys reported hiring a graphics consultant for more than 20% of their cases. By contrast, three-quarters of plaintiffs' lawyers report never having hired anyone to design or produce courtroom graphics.

The one young lawyer, who indicated that she uses trial and graphics consultants in more than half of her cases, handles both criminal and civil defense cases.

From What to Where

We have now discovered differences in consultant usage among lawyers who handle different types of cases. Civil defense lawyers make much more use of trial consultants and graphics consultants than do their less well financed colleagues. We also know that in some areas of tort law, the defense wins 90% of jury trials. It would be purely speculative to connect this success rate with use of trial and graphics consulting services, but it is suggestive enough to warrant further study.

Fortunately, with the exception of criminal defense attorneys, the lawyers who completed this survey are distributed throughout the country. This will provide me an opportunity to explore whether there are regional variations in trial and graphics consulting usage. I will have to be mindful, however, of the trends I have uncovered with respect to seniority and practice area. If the lawyers in one region seem to hire a lot of graphics consultants, I will need to make sure that it is not simply because they are all civil defense attorneys.

Finally, I wish to explore whether there are any systematic variations in the types of services for which attorneys hire consultants. Is it mostly for jury selection in one region and mock trials in another? Do certain types of attorneys hire consultants to help with witness preparation more than others? I will address these questions, along with geographic variations, in my next post.

Monday, March 08, 2010

Trial Consultant Usage All Over the Map

The Survey at a Glance

Several weeks ago, I was in conversation with a colleague about the different approaches taken by various lawyers with respect to using trial consulting services. Some lawyers don't see any use for our expertise, or believe that their clients just can't afford to use us. Some lawyers employ the occasional consultant to run jury research, but really want a project manager more than an expert in jury behavior. There are many lawyers who will call in a trial consultant for the occasional case when she experiences uncertainty regarding a particular jury issue. Finally, there are a handful of lawyers who work with a trial consultant on virtually every case, finding their expertise to be well-worth the investment.

I commented, rather off-handedly, that I thought there were probably lots of regional differences. I think that differences in procedural rules (e.g. attorney conducted voir dire, ad damnum usage) and legal culture result in their being jurisdictions where litigators make great use of trial consulting services and others where attorneys rarely hire trial consultants.

I soon realized that this was a testable hypothesis. So, I went off to SurveyMonkey.com and crafted a short survey to investigate which litigators hire trial consultants (and courtroom graphics consultants) and which ones don't. I included questions about how long each respondent has been a lawyer, what kind of cases she handles, and where her office is located.

The survey is still live and I will be analyzing the data long into the future. So, if you are a trial lawyer, and you have not yet filled out the survey, please do so here. It only takes about 2 minutes and it is completely anonymous.

Spreading the Word

As many of you know, I am extremely active on LinkedIn. I posted a notice about the survey as a discussion on many of the groups to which I belong. I also tweeted an invitation to participate on several occasions. Finally, I sent out an email to everyone on my professional distribution list (formerly used for my newsletter, before it became this blog). I would conservatively estimate that at least one invitation to participate was seen by over 500 litigators.

Well, I wasn't offering to pay respondents. I wasn't raffling off an iPod or a timeshare in Maui. Lawyers are used to billing clients for every 6 minutes of their time and they are extremely sensitive to concerns about online privacy. So, the response rate was not great.

As of today, 37 people have completed the survey. Of these, 5 indicated that they were not lawyers (although a few might work for law firms in some other capacity). 28 of the respondents indicated that they heard about the survey on LinkedIn. 8 found out through email, and 1 via Twitter. Needless to say, any conclusions to be drawn from such a small sample will be speculative in nature. I do hope, however, that the results will give us something to build upon in the future.

Preliminary Results: Trial Consulting

I was careful in the survey to differentiate between "Trial Consulting" services, which deal with the social psychology of jury behavior (jury selection, witness preparation, focus group studies, etc.) and "Trial Graphics" services, which include illustrations and animations for courtroom use. Here is a graph illustrating the frequency with which survey respondents employ "Trial Consulting" services, in terms of percentage of cases.

About half of the survey's respondents have used a graphics consultant for at least one case. I think that most of us would expect trial graphics to be used more frequently than trial consulting. The discrepancy between this expectation and my data undoubtedly arises from the participation of many of my clients. Several of these attorneys, especially those doing criminal defense work, have benefitted from my active pro bono practice. They have not had similar access to affordable trial graphics assistance.

Do the Same Lawyers use Both Services?

As I mention above, there is reason to believe that at least a handful of attorneys would make use of trial consulting services, but not graphics consulting ones. Is this a common occurrence? The graph below answers this question.

As a general rule, lawyers either use litigation consulting services of both types, or they don't use either. Only a few litigators reported using graphics consultants but not trial consultants. I find this result a bit surprising. While I did not ask respondents about the size of their firms, I would expect that this sample is heavily weighted towards small and mid-sized firms, whose attorneys tend to be heavier users of LinkedIn. Lawyers from large firms (many hundreds of lawyers) are unlikely to have found their way to my survey. Such firms handle huge IP and business litigation cases, in which courtroom exhibits are sophisticated and plentiful. The underrepresentation of such litigators from my sample have certainly affected the nature of my results.

Questions to be Explored

These preliminary results are certainly interesting. We have responses from many attorneys who have used a trial or graphics consultant to help with jury trials. Who are they? What kind of work do they do? Where do they practice? These are the more nuanced questions that I will be addressing in my next two posts.

In addition to surveying experience with consultants, I asked respondents about which kinds of services they had hired consultants to perform. I provided an extensive list, including jury selection, witness preparation, illustrations, animations and more. I will explore in a future post trends in the data, with respect to which trial lawyers made use of which services.

So, stay tuned! Same Bat-time, same Bat-channel.

And remember, it's not too late to contribute your own experience to the data. Take the survey here.

Several weeks ago, I was in conversation with a colleague about the different approaches taken by various lawyers with respect to using trial consulting services. Some lawyers don't see any use for our expertise, or believe that their clients just can't afford to use us. Some lawyers employ the occasional consultant to run jury research, but really want a project manager more than an expert in jury behavior. There are many lawyers who will call in a trial consultant for the occasional case when she experiences uncertainty regarding a particular jury issue. Finally, there are a handful of lawyers who work with a trial consultant on virtually every case, finding their expertise to be well-worth the investment.

I commented, rather off-handedly, that I thought there were probably lots of regional differences. I think that differences in procedural rules (e.g. attorney conducted voir dire, ad damnum usage) and legal culture result in their being jurisdictions where litigators make great use of trial consulting services and others where attorneys rarely hire trial consultants.

I soon realized that this was a testable hypothesis. So, I went off to SurveyMonkey.com and crafted a short survey to investigate which litigators hire trial consultants (and courtroom graphics consultants) and which ones don't. I included questions about how long each respondent has been a lawyer, what kind of cases she handles, and where her office is located.

The survey is still live and I will be analyzing the data long into the future. So, if you are a trial lawyer, and you have not yet filled out the survey, please do so here. It only takes about 2 minutes and it is completely anonymous.

Spreading the Word

As many of you know, I am extremely active on LinkedIn. I posted a notice about the survey as a discussion on many of the groups to which I belong. I also tweeted an invitation to participate on several occasions. Finally, I sent out an email to everyone on my professional distribution list (formerly used for my newsletter, before it became this blog). I would conservatively estimate that at least one invitation to participate was seen by over 500 litigators.

Well, I wasn't offering to pay respondents. I wasn't raffling off an iPod or a timeshare in Maui. Lawyers are used to billing clients for every 6 minutes of their time and they are extremely sensitive to concerns about online privacy. So, the response rate was not great.

As of today, 37 people have completed the survey. Of these, 5 indicated that they were not lawyers (although a few might work for law firms in some other capacity). 28 of the respondents indicated that they heard about the survey on LinkedIn. 8 found out through email, and 1 via Twitter. Needless to say, any conclusions to be drawn from such a small sample will be speculative in nature. I do hope, however, that the results will give us something to build upon in the future.

Preliminary Results: Trial Consulting

I was careful in the survey to differentiate between "Trial Consulting" services, which deal with the social psychology of jury behavior (jury selection, witness preparation, focus group studies, etc.) and "Trial Graphics" services, which include illustrations and animations for courtroom use. Here is a graph illustrating the frequency with which survey respondents employ "Trial Consulting" services, in terms of percentage of cases.

Trial Consulting Service Usage: Full Sample

As you can see from the figure, very few attorneys indicated that they used trial consultants for more than 20% of their cases. The interesting distinction here seems to be between those litigators who sometimes use trial consultants and those that never do. For my sample, approximately 60% of respondents indicated they had ever used a trial consultant.

There are a couple of reasons to be skeptical of these numbers. First, I would expect that participating in the survey would be more interesting to those lawyers with some familiarity with trial consulting. As such, I thought that most of the respondents would be lawyers who had worked with trial consultants in the past. Second, the publication of the survey was heavily skewed towards people who know me in some capacity. Of those, I would expect that my clients would be particularly inclined to help me out by filling out the survey. (Based on zip codes and other survey responses, I am fairly sure that about a half-dozen respondents are, in fact, clients of mine.) In light of these factors, I believe that these results probably overestimate trial consultant usage in the general population.

I am located in Massachusetts and most of my clients are from New England. This is reflected in the large number of respondents from this region (9). That said, it is gratifying to see that the remainder of the respondents come from all over the United States. I will be discussing regional variations in the data in my next post.

Preliminary Results: Graphics Consulting

I am what I refer to as a "behavioral" trial consultant. While I advise clients on the kinds of exhibits they might employ at trial, and evaluate the utility of the graphs and illustrations they already have, I do not provide trial graphics services. As such, the responses with respect to graphics consulting are probably less skewed by the participation of my own clients. The graph below shows graphics consulting usage for the complete sample.

Graphics Consulting Service Usage: Full Sample

About half of the survey's respondents have used a graphics consultant for at least one case. I think that most of us would expect trial graphics to be used more frequently than trial consulting. The discrepancy between this expectation and my data undoubtedly arises from the participation of many of my clients. Several of these attorneys, especially those doing criminal defense work, have benefitted from my active pro bono practice. They have not had similar access to affordable trial graphics assistance.

Do the Same Lawyers use Both Services?

As I mention above, there is reason to believe that at least a handful of attorneys would make use of trial consulting services, but not graphics consulting ones. Is this a common occurrence? The graph below answers this question.

Joint Usage of Trial and Graphics Consulting Services

As a general rule, lawyers either use litigation consulting services of both types, or they don't use either. Only a few litigators reported using graphics consultants but not trial consultants. I find this result a bit surprising. While I did not ask respondents about the size of their firms, I would expect that this sample is heavily weighted towards small and mid-sized firms, whose attorneys tend to be heavier users of LinkedIn. Lawyers from large firms (many hundreds of lawyers) are unlikely to have found their way to my survey. Such firms handle huge IP and business litigation cases, in which courtroom exhibits are sophisticated and plentiful. The underrepresentation of such litigators from my sample have certainly affected the nature of my results.

Questions to be Explored

These preliminary results are certainly interesting. We have responses from many attorneys who have used a trial or graphics consultant to help with jury trials. Who are they? What kind of work do they do? Where do they practice? These are the more nuanced questions that I will be addressing in my next two posts.

In addition to surveying experience with consultants, I asked respondents about which kinds of services they had hired consultants to perform. I provided an extensive list, including jury selection, witness preparation, illustrations, animations and more. I will explore in a future post trends in the data, with respect to which trial lawyers made use of which services.

So, stay tuned! Same Bat-time, same Bat-channel.

And remember, it's not too late to contribute your own experience to the data. Take the survey here.

Thursday, February 04, 2010

Plethora of reasons for defense counsel to argue damages at trial

Hey you! Pay attention!

In the latest issue of The Jury Expert, Jeri Kagel has contributed a very thoughtful article, entitled "Damages: The Defense Attorney's Dilemma." In her article, Jeri presents in stark terms the ambivalence that most civil defense attorneys experience regarding discussing damages before a jury. All of us in the trial consulting profession encounter clients who are stubborn about certain things.

We trial consultants have read the experimental research on the topic. We have run our own studies. We know that arguing damages at trial is a winning strategy for defense attorneys. It generally has a negligible impact on the liability decision and can have a profound impact on the damage award.

Don't live in fear! Come into the light!

In fact, our frustration with our clients on this point has led many of us to write newsletter articles, editorials and/or blog posts about this very topic.

From myself, "Getting Defense Counsel to talk about damages is like conducting an intervention."

From Aaron Abbott, "New Research on Damage Awards: Do jurors split the difference?"

From Sarah Murray, "Strategies for minimizing damages in high damages cases."

From Jeffrey Frederick, "Searching for rocks in the Channel: Pretesting your case before trial."

I actually managed to convince a client to run a mock trial experiment on the question of arguing damages at trial. We had two panels who all watched the same mock trial for a day-and-a-half. We then separated them for closing arguments. To one group, defense counsel said nothing about damages. To the other, defense counsel added one paragraph, discussing the unreasonableness of plaintiff's award request, and suggesting a more appropriate figure.

Much to my client's surprise, the panel that had heard defense arguments about damages did not once discuss this fact with respect to the liability question. That is, when deciding whether the defendant was liable, not once did anyone point out that defense counsel had raised the damages issue in his closing.

The differences did emerge when we asked the two panels to calculate a damage award for the plaintiff. The panel that had heard a counter-argument on damages from defense counsel chose an award half the size arrived at by the panel that only heard plaintiff's arguments about damages. The provision of a "counter-anchor" for damage award calculations can substantially reduce the size of such an award.

Don't put off until tomorrow what you can argue today.

A significant contribution of Jeri's article in The Jury Expert is a cataloging of opportunities for defense counsel to introduce arguments about damages throughout the trial. The typical question a defense attorney confronts is, "Should I mention damages in my closing argument?" Jeri points out that this dilemma should not be so narrowly defined. Defense counsel should include questions during voir dire about how prospective jurors are likely to think about calculating damage awards. She advocates including arguments in opening statements that help "teach" jurors how to evaluate critically testimony about damages.

A more comprehensive strategy for dealing with the damages issue allows defense counsel to influence juror decisions about damages without having to resort to the "arguing in the alternative" tactic. (My client didn't do anything wrong, but if you decide he did, it wasn't really that bad.) In addition, in jurisdictions that do not permit an ad damnum (specific monetary request from the plaintiff), defense counsel can implement those strategies most appropriate to the local rules.

There is one big lesson one should glean from the experimental literature and the musings of trial consultants. Don't punt on damages. Ceding to the plaintiff total control over the way in which the jury discusses damages is a recipe for disaster.

In the latest issue of The Jury Expert, Jeri Kagel has contributed a very thoughtful article, entitled "Damages: The Defense Attorney's Dilemma." In her article, Jeri presents in stark terms the ambivalence that most civil defense attorneys experience regarding discussing damages before a jury. All of us in the trial consulting profession encounter clients who are stubborn about certain things.

"I never make opening statements."

"I don't depose opposing experts because I don't want 'em to know what's coming."

"I don't like my expert to use visual aids because it distracts the jury from what he's saying."By a large margin, the most common immovable object is, "I don't argue damages at trial."

We trial consultants have read the experimental research on the topic. We have run our own studies. We know that arguing damages at trial is a winning strategy for defense attorneys. It generally has a negligible impact on the liability decision and can have a profound impact on the damage award.

Don't live in fear! Come into the light!

In fact, our frustration with our clients on this point has led many of us to write newsletter articles, editorials and/or blog posts about this very topic.

From myself, "Getting Defense Counsel to talk about damages is like conducting an intervention."

From Aaron Abbott, "New Research on Damage Awards: Do jurors split the difference?"

From Sarah Murray, "Strategies for minimizing damages in high damages cases."

From Jeffrey Frederick, "Searching for rocks in the Channel: Pretesting your case before trial."

I actually managed to convince a client to run a mock trial experiment on the question of arguing damages at trial. We had two panels who all watched the same mock trial for a day-and-a-half. We then separated them for closing arguments. To one group, defense counsel said nothing about damages. To the other, defense counsel added one paragraph, discussing the unreasonableness of plaintiff's award request, and suggesting a more appropriate figure.

Much to my client's surprise, the panel that had heard defense arguments about damages did not once discuss this fact with respect to the liability question. That is, when deciding whether the defendant was liable, not once did anyone point out that defense counsel had raised the damages issue in his closing.

The differences did emerge when we asked the two panels to calculate a damage award for the plaintiff. The panel that had heard a counter-argument on damages from defense counsel chose an award half the size arrived at by the panel that only heard plaintiff's arguments about damages. The provision of a "counter-anchor" for damage award calculations can substantially reduce the size of such an award.

Don't put off until tomorrow what you can argue today.

A significant contribution of Jeri's article in The Jury Expert is a cataloging of opportunities for defense counsel to introduce arguments about damages throughout the trial. The typical question a defense attorney confronts is, "Should I mention damages in my closing argument?" Jeri points out that this dilemma should not be so narrowly defined. Defense counsel should include questions during voir dire about how prospective jurors are likely to think about calculating damage awards. She advocates including arguments in opening statements that help "teach" jurors how to evaluate critically testimony about damages.

A more comprehensive strategy for dealing with the damages issue allows defense counsel to influence juror decisions about damages without having to resort to the "arguing in the alternative" tactic. (My client didn't do anything wrong, but if you decide he did, it wasn't really that bad.) In addition, in jurisdictions that do not permit an ad damnum (specific monetary request from the plaintiff), defense counsel can implement those strategies most appropriate to the local rules.

There is one big lesson one should glean from the experimental literature and the musings of trial consultants. Don't punt on damages. Ceding to the plaintiff total control over the way in which the jury discusses damages is a recipe for disaster.

Thursday, January 28, 2010

Defense must play blame game in Rebecca Riley murder trial

The tragedy

Rebecca Riley, age 4, died in the throes of pneumonia, while very heavily medicated on Depakote and Clonidine, intended to treat ADHD and bipolar disorder. Her parents, Carolyn and Michael, are on trial for Rebecca's murder (Read about the trial here). According to prosecutors, Carolyn and Michael routinely lied to doctors in an effort to get all their children prescribed strong drugs, eventually finding a Boston psychiatrist willing to believe them and hand out ever-stronger doses. Prosecutors claim that the Rileys cared only about making their children easy to manage, regardless of any adverse health consequences, and collecting federal disability benefits. Eventually, after being given extremely high dosages of these powerful drugs, even by adult patient standards, Rebecca died in her parents' home.

When a tragedy like this strikes, it is quite natural for ordinary people to want to assign blame. Someone must have been responsible and that person should be held accountable. Why is there such a palpable need to assign blame? It stems from several reinforcing psychological phenomena.

The human need for answers and accountability

The first is a natural aversion to reminders of one's own mortality. We don't like to feel vulnerable. Therefore, when bad things -- deadly things -- happen to others, our brains automatically generate reasons why such threats aren't dangerous to us. A standard response is to generate distinctions between the victim's circumstances and our own. Some distinctions are circumstantial, while others are directed at choices made by the victim or some other responsible party.

A second psychological response to such a tragedy is to shrink back from the randomness of a bad event. We don't like to think that we are not in control of our own lives. We like to think that our own actions and choices will insure our own well-being. Therefore, people tend to overestimate the control that someone else could have exercised over a difficult situation. This is because any bystander would like to believe that, had she been in the same situation, she would have been able to stop the tragedy from occurring.

Finally, as I have written about on a number of occasions, hindsight bias is always at play when rare events take place. Ordinary people have a great deal of trouble processing the true chance of very unlikely events. The numbers just get too small for the brain to easily process. (What does a 1-in-500,000 chance really look like?). Also, the cognitive availability of an event (after all, the event is the focus of the trial) makes it seem more likely to have occurred. This tendency to overestimate the likelihood of an event also results in people overestimating the events predictability and preventability. An odd second-order effect is that the more peculiar the circumstances, the more likely people are to assume that a tragedy could have been averted.

Jurors are not experts in risk assessment. They typically don't have degrees in statistics or bioinformatics. They are ordinary folks, tasked with processing some very foreign circumstances. As such, they will be subject to the kinds of cognitive tendencies outlined above. The Rebecca Riley death is a very strange story. The loss of a young child is every parent's worst nightmare. The world of pediatric psychiatry seems very alien to all of the jurors. All of these factors will combine to make the jurors very eager to find someone to blame for this horrible tragedy. Once they assign blame, they can go back to believing that such a thing could never happen to them.

What should the defense team do?

This is the environment in which Carolyn and Michael Riley are being tried. One defense strategy might be to portray this death to the jury as an unfortunate accident. For the reasons I outline above, I think this will be an extremely tough sell. A better strategy would be to try to deflect blame onto others. Let the jurors have their culprit, but try to convince at least some of them that the culprit is someone other than the defendant.

The defense team took a sensible first step in this direction by requesting separate trials for the two parents. This allows each to deflect responsibility to the other. The key for Carolyn's legal team is to get at least some on the jury to assign more responsibility to her husband than to her. Frankly, based on what we have heard so far, such a tactic would seem more promising for Michael's defense than for Carolyn's.

The second likely candidate for deflected blame is the psychiatrist who prescribed the medication. Dr. Kayoko Kufuji has now testified in Carolyn's trial. While she came across as detached and somewhat clueless, which points to her own negligence, the prosecution did a very good job of showing how Dr. Kufuji relied very heavily on Carolyn Riley's own characterizations of her children, when making her diagnoses. As such, Kufuji's failures seem largely the result of Carolyn Riley's dishonesty and manipulation.

The third candidate for deflected blame, and the one I think is most likely to garner some sympathy with jurors, is Carolyn Riley's own mental state. The prosecutor is trying to paint a picture of a calculating, manipulative mother who happily endangered her children to keep them docile and to collect federal disability checks. The defense might just gain some traction by telling the jury that she was mentally unbalanced. There are official conditions, like Munchausen-by-proxy, where parents imagine or invent illnesses in their children to fulfill a pathological need for attention. Alternatively, the defense could attribute her extreme behavior to the abusive treatment by her husband. Michael Riley has been banned from a prior residence due to violent behavior and Carolyn Riley once took out a restraining order against her husband, ostensibly to protect her children. Under such a scenario, the defense can contend that the system let Carolyn down, enabling behavior that was not only self-destructive, but also endangered the Riley children.

Will it work?

Jurors are generally skeptical of victimization arguments like the one I outline above, but it seems the best strategy in a case like this. There is a documented history of spousal abuse. Many authority figures who interacted with Carolyn and her children failed to take official action. Remember that only one juror needs to be convinced that Carolyn Riley wasn't completely responsible for her own actions to avoid a murder conviction.

The defense strategy needs to be focused on getting Carolyn's sanity into the discussion in the jury room. They need to open the door for those who might be inclined to take pity on her. I rather doubt that the jury will initially be unanimous in its evaluation of her culpability. Arguments will be heated. Tears will be shed. Playing up the defendant's mental instability might not keep her out of jail, but I could see a conviction on a lesser included offense, such as involuntary manslaughter. Given what has transpired in court so far, that would probably be considered a victory for the defense.

Rebecca Riley, age 4, died in the throes of pneumonia, while very heavily medicated on Depakote and Clonidine, intended to treat ADHD and bipolar disorder. Her parents, Carolyn and Michael, are on trial for Rebecca's murder (Read about the trial here). According to prosecutors, Carolyn and Michael routinely lied to doctors in an effort to get all their children prescribed strong drugs, eventually finding a Boston psychiatrist willing to believe them and hand out ever-stronger doses. Prosecutors claim that the Rileys cared only about making their children easy to manage, regardless of any adverse health consequences, and collecting federal disability benefits. Eventually, after being given extremely high dosages of these powerful drugs, even by adult patient standards, Rebecca died in her parents' home.

When a tragedy like this strikes, it is quite natural for ordinary people to want to assign blame. Someone must have been responsible and that person should be held accountable. Why is there such a palpable need to assign blame? It stems from several reinforcing psychological phenomena.

The human need for answers and accountability

The first is a natural aversion to reminders of one's own mortality. We don't like to feel vulnerable. Therefore, when bad things -- deadly things -- happen to others, our brains automatically generate reasons why such threats aren't dangerous to us. A standard response is to generate distinctions between the victim's circumstances and our own. Some distinctions are circumstantial, while others are directed at choices made by the victim or some other responsible party.

A second psychological response to such a tragedy is to shrink back from the randomness of a bad event. We don't like to think that we are not in control of our own lives. We like to think that our own actions and choices will insure our own well-being. Therefore, people tend to overestimate the control that someone else could have exercised over a difficult situation. This is because any bystander would like to believe that, had she been in the same situation, she would have been able to stop the tragedy from occurring.

Finally, as I have written about on a number of occasions, hindsight bias is always at play when rare events take place. Ordinary people have a great deal of trouble processing the true chance of very unlikely events. The numbers just get too small for the brain to easily process. (What does a 1-in-500,000 chance really look like?). Also, the cognitive availability of an event (after all, the event is the focus of the trial) makes it seem more likely to have occurred. This tendency to overestimate the likelihood of an event also results in people overestimating the events predictability and preventability. An odd second-order effect is that the more peculiar the circumstances, the more likely people are to assume that a tragedy could have been averted.

Jurors are not experts in risk assessment. They typically don't have degrees in statistics or bioinformatics. They are ordinary folks, tasked with processing some very foreign circumstances. As such, they will be subject to the kinds of cognitive tendencies outlined above. The Rebecca Riley death is a very strange story. The loss of a young child is every parent's worst nightmare. The world of pediatric psychiatry seems very alien to all of the jurors. All of these factors will combine to make the jurors very eager to find someone to blame for this horrible tragedy. Once they assign blame, they can go back to believing that such a thing could never happen to them.

What should the defense team do?

This is the environment in which Carolyn and Michael Riley are being tried. One defense strategy might be to portray this death to the jury as an unfortunate accident. For the reasons I outline above, I think this will be an extremely tough sell. A better strategy would be to try to deflect blame onto others. Let the jurors have their culprit, but try to convince at least some of them that the culprit is someone other than the defendant.

The defense team took a sensible first step in this direction by requesting separate trials for the two parents. This allows each to deflect responsibility to the other. The key for Carolyn's legal team is to get at least some on the jury to assign more responsibility to her husband than to her. Frankly, based on what we have heard so far, such a tactic would seem more promising for Michael's defense than for Carolyn's.

The second likely candidate for deflected blame is the psychiatrist who prescribed the medication. Dr. Kayoko Kufuji has now testified in Carolyn's trial. While she came across as detached and somewhat clueless, which points to her own negligence, the prosecution did a very good job of showing how Dr. Kufuji relied very heavily on Carolyn Riley's own characterizations of her children, when making her diagnoses. As such, Kufuji's failures seem largely the result of Carolyn Riley's dishonesty and manipulation.

The third candidate for deflected blame, and the one I think is most likely to garner some sympathy with jurors, is Carolyn Riley's own mental state. The prosecutor is trying to paint a picture of a calculating, manipulative mother who happily endangered her children to keep them docile and to collect federal disability checks. The defense might just gain some traction by telling the jury that she was mentally unbalanced. There are official conditions, like Munchausen-by-proxy, where parents imagine or invent illnesses in their children to fulfill a pathological need for attention. Alternatively, the defense could attribute her extreme behavior to the abusive treatment by her husband. Michael Riley has been banned from a prior residence due to violent behavior and Carolyn Riley once took out a restraining order against her husband, ostensibly to protect her children. Under such a scenario, the defense can contend that the system let Carolyn down, enabling behavior that was not only self-destructive, but also endangered the Riley children.

Will it work?

Jurors are generally skeptical of victimization arguments like the one I outline above, but it seems the best strategy in a case like this. There is a documented history of spousal abuse. Many authority figures who interacted with Carolyn and her children failed to take official action. Remember that only one juror needs to be convinced that Carolyn Riley wasn't completely responsible for her own actions to avoid a murder conviction.